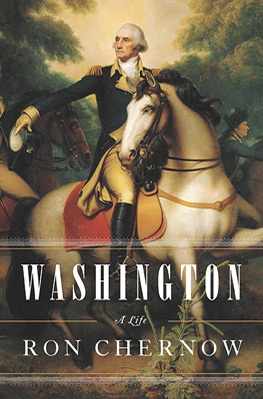

Washington: A Life

By Ron Chernow

928 pages paperback, Sept. 2011 by Penguin Books

ISBN-13: 978-0143119968

Reviewed by Gila Hayes

For my Independence Day reading about our nation’s founders, the book I chose was a whopping 900+ page biography of our nation’s first president written by Ron Chernow. In Washington: A Life, the biographer replaces the image of a remote, austere commander in chief suggested by paintings and history books with a very human but determined individual who vowed not to be ruled by his temper or his social reticence. Of course, that Washington had flaws is not surprising; I was not aware of characteristics the book describes and came away feeling I knew more about the person he was.

Born to a Virginia landowner, the future president was only a boy when his father died. Lacking formal education, Washington hoped to join England’s royal navy, but his domineering mother prohibited it. Instead, he earned recognition in the Virginia Regiment during the Indian Wars. There, under the command of British Major General Braddock, he “acquired a powerful storehouse of grievances that would fuel his later rage with England,” the biographer notes.

When England tried to recoup the expense of the Indian Wars by taxing essential commodities, the colonials revolted. Washington, serving in the Virginia House of Burgesses, was reluctant to foment rebellion and discouraged early acts of insurrection. “Washington knew how indomitable the British military machine was and how quixotic a full-scale revolution would be,” observes Chernow. By 1774, even Washington was fed up. He supported bans on imports of English goods and travelled to Philadelphia as a delegate to the First Continental Congress.

Washington was uncomfortable among the other delegates. “Taciturn Washington, at forty-two, found himself in an assembly of splendid talkers who knew how to pontificate on every subject.” His silent demeanour inspired confidence, and his military prowess was well-known. Patriots looked to him for leadership even as he hoped to avoid “the horrors of civil discord.” Nonetheless, bowing to public pressure, Washington accepted command of four companies of militiamen whom he encouraged to train and study military science.

When British frigates disgorged soldiers onto American soil, Washington agreed to command the Continental Army. Worried about appearing to exploit the revolution for personal gain, he refused a salary. His preoccupation with his reputation is a repeating theme throughout this biography. He probably shouldn’t have worried; congress failed to pay its army or the officers more often than not, and even when the army disbanded in the fall of 1783, there was no money in the federal treasury to pay its officers and Washington, never good with his own budget, was near personal bankruptcy.

Washington’s war councils reveal character traits I’d not read about before. His was a consultive leadership style, and he was slow to make decisions without hearing all sides. Once he made up his mind, though, Washington was nearly impossible to dissuade.

From fighting for England during the Indian Wars, Washington knew the British Army could throw nearly endless men and munitions into the fray. By contrast, the Continental Army fought the entire war with severe food shortages, were poorly clothed and sheltered, sometimes armed only with spears and arrows when there was not enough gunpowder. His soldiers were committed to only a year’s service. When the army went unpaid, Washington had endless difficulty keeping troops. “For Washington, the failure to create a permanent army early in the war was the original sin from which the patriots rarely recovered,” the biographer writes. This influenced Washington’s later preference for a strong central government.

Telling of Washington’s experiences during famous Revolutionary War battles, Chernow portrays American troops numbering only several thousand battling tens of thousands of English soldiers and mercenaries. If the British army’s superior numbers and better armament didn’t kill you, the camps' lack of sanitation and disease likely would. By mid-August of 1775, over a quarter of Washington’s troops were sick and outnumbered 4:1, the biographer observes. Conditions at Valley Forge, the battle for Long Island, and the Siege of Yorktown, to name only a few, made the eventual victory truly remarkable.

Out of economic necessity, American farmers sold produce to the better-funded British army. Washington deplored wartime plundering of livestock and supplies from citizens and punished his starving men when they stole food. When the French were finally persuaded to join the fight, the dreadful condition of Washington’s army dismayed the new ally. The French treated Washington disrespectfully but loaned much-needed money and temporarily dispatched part of their West Indies fleet, making the Yorktown victory one of the war’s most decisive.

If the French maltreated Washington, backstabbing was worse among Americans vying for top military positions, and subordinates sabotaged him. Several colonists remained loyal to England; others aimed to profit from the war by backing the presumptive winner. Who can forget the story of the spy Benedict Arnold? Chernow writes an interesting chapter that tells how Arnold’s wife deceived Washington, Lafayette and Hamilton to assure her traitorous husband’s escape.

Washington feared “massive desertion or even full-blown defection to the British”, who lured American soldiers to abandon the revolution. Without funds for food and supplies, the cause seemed doomed. Providentially, the Americans began to win in the South, but an empty treasury made Washington anxious that the revolution would fizzle out before winning independence.

Finally, on November 1, 1783, word reached Washington of the treaty that ended the war. He resigned his commission and spent several years working his plantation and other lands before bowing to pressure to lead the Virginia delegation at the Constitutional Convention in 1786. Shays’ Rebellion demonstrated that without substantial reforms, a civil war was likely. He went to Philadelphia, where, with Ben Franklin too sick to serve, he reluctantly assumed leadership of the convention. The non-partisan role fit Washington’s “discreet nature” well, and Chernow writes that Washington’s leadership “reassured Americans that the delegates were striving for the public good” despite considerable suspicion. Outside the convention hall, he shrugged off the role of impartial arbiter, conversing in tea rooms and taverns with the other delegates and the locals.

After the constitution was ratified, Washington’s name arose as the natural choice for president. He was conflicted but felt he dared not seek advice for fear of appearing to campaign for election. Lafayette, Hamilton and others endorsed him, and the public liked the idea because he had no children to create a dynastic monarchy. Chernow writes that accepting the presidency was Washington’s most painful decision. He estimated that he could serve two years, then hand off the presidency to another; little did he know eight years of “arduous service” would follow the electoral college’s unanimous vote for him.

Washington’s presidency relied on numerous advisors – Adams, Madison, Hamilton, Jay and others. “The hallmark of his administration would be an openness to conflicting ideas,” Chernow writes. He appointed strong, intelligent men to his cabinet and was unafraid to ask for guidance from them. His administration was a “model of smooth efficiency,” although he demanded much of his subordinates. “Washington encouraged the free, creative interplay of ideas, setting a cordial tone of collegiality. He prized efficiency and close attention to detail.” Washington wrote, “Much was to be done by prudence, much by conciliation, much by firmness.” He preferred deliberation to fast decisions, valued silence over speech and hated boasting.

Taxation to pay the government’s debts caused the first big row in the cabinet. Chernow details additional growing pains the new nation faced, including great distress over slavery, relocating the capital, creating a federal treasury, bloodshed with the Indians over land, and foreign policy, to name only a few. Washington aspired to operate above backbiting and political power-mongering, seeing his leadership role as “surmounting partisan interests,” but was sorely challenged to meet that ideal.

A “venomous split” between the Federalists and the Republicans pressured the 60-year-old Washington to stay on for a second term, a period complicated by war between the English and the French. Despite a masterful neutrality proclamation, Washington’s cabinet fell prey to manipulation, especially the French foreign minister. The European war reminded the risks new nation faced due to a weak army and nonexistent navy. Funds were authorized for ships and soldiers, but that alarmed those who feared “an oppressive military establishment that might be directed against homegrown dissidents.”

That threat manifested in the Whiskey Rebellion of 1791-94, which Washington viewed as a test of the constitution, saying it would show if a few citizens could dictate to the entire nation. “He faulted the insurgents for failing to recognize that the excise law was not a fiat, issued by an autocratic government, but a tax voted by their lawful representatives.” When it was over, he gave clemency to all but two of the rebellion’s leaders, but his actions further alienated him from Madison and Jefferson who condemned Washington’s speech against “societies” acting against the government. They said he had abandoned his nonpartisan ideals and joined the Federalists. Was the outcome that bad? “Given the giant scale of the protest and the governmental response, there had been remarkably few deaths … showing it [the government] could contain large-scale disorder without sacrificing constitutional niceties,” Chernow writes.

By 1797, Washington was truly ready to retire to his beloved Mount Vernon. Instead of addressing Congress, he submitted his farewell speech directly to the American citizens, printed first in the Philadelphia newspapers. In his message, he challenged Americans to be better citizens, support the Union, and endorse a strong central government. “For opponents who had spent eight years harping on Washington’s supposed monarchical obsessions, his decision to step down could only have left them in a dazed state of speechless confusion,” Chernow writes.

The first president’s remarkable “catalogue of accomplishments” is crowned by showing “a disbelieving world that republican government could prosper without being spineless or disorderly or reverting to authoritarian rule. In surrendering the presidency after two terms and overseeing a smooth transition of power, Washington had demonstrated that the president was merely the servant of the people,” the biographer concludes.

Several chapters about Washington’s return to Mount Vernon and his later life debunk some of the myths that have risen up around our first president. Chernow writes of Washington’s largely unsuccessful attempt to distance himself from politics, continued budgetary problems on his properties, and his evolving relationship with Jefferson, Hamilton, Knox and others.

I learned many new details about the Father of our Country in this long biography and gained a new appreciation for his sacrifices and determination.